Some 85 years ago, in 1936, Emperor Haile Selassie I stood before the General Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva to make a speech that would make him an icon of the struggle against fascism. At the time, the emperor had been driven out of his country by the forces of Mussolini, who exterminated his poorly armed defense forces, thus bringing to an end the only standing, independent nation of Africa. During the speech, Haile Selassie started by describing the gruesome way Mussolini’s fascist army exterminated civilian and military targets using the poisonous mustard gas, which was banned under the Geneva Protocol, of which both Ethiopia and Italy were signatories.

Haile Selassie beseeched for help, arguing that the League’s promise of a collective security rested upon “the confidence that each State is to place in international treaties. It is the value of promises made to small States that their integrity and their independence shall be respected and ensured.” By abandoning its weaker members in times of their need, he argued, the League of Nations was sacrificing its “international morality.”

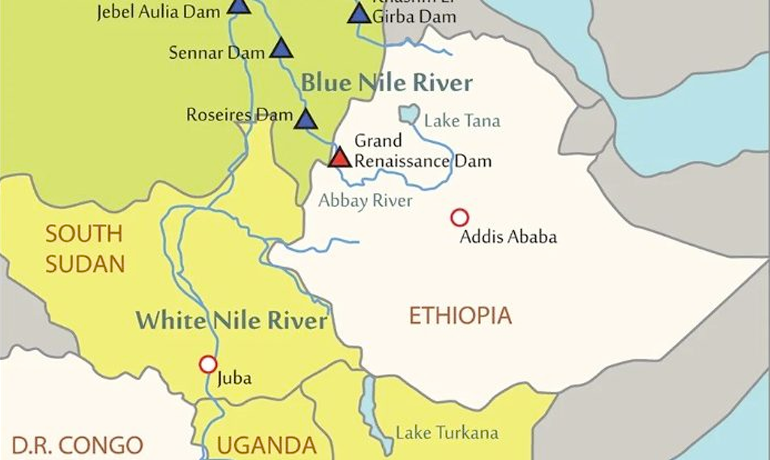

But the League of Nations was in no mood to take a moral high ground and protect small states like Ethiopia. The emperor’s words landed on deaf ears as the European powers of the time, France and Britain, were keen to appease Mussolini to avoid his inevitable alliance with Hitler. Three years down the line, the Second World War erupted as the League of Nations, having lost its credibility, failed to avoid further escalation. European states, including France, started to crumble under the joint forces of Fascism and Nazism. A dam dispute at the U.N. There is an unavoidable parallel between that decades-old event in Ethiopian history, and what happened at the United Nations Security Council meeting on June 29, 2020. The Security Council convened the open hearing to discuss the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile, under an agenda of “Peace and Security in Africa”. It was an unusual meeting, perhaps the first ever assembled over a dispute over a transboundary river. Although reaching an agreement has remained elusive for years now, peaceful negotiations were ongoing with renewed impetus under the auspices of the African Union. It was hence a puzzle how a development project like the GERD ended up becoming an agenda for the world’s highest organ of international peace and security. Egypt had apparently used the force of American diplomatic power to summon a hearing at the Security Council, through a process that contravened established practices for virtual meetings during the Covid-19 lockdown. It was only when Egypt’s foreign minister, Mr. Sameh Shoukry, made his speech that the security grounds of this meeting became apparent. In a blistering speech that betrayed desperation, he underscored his country’s serious dependence on the Nile waters. The Foreign Minister depicted Ethiopia’s Blue Nile dam as a malicious project that is set to ignite regional destabilization, undermine Egypt’s stability and wreaking socio-economic havoc from crime to mass migration. He painted “a looming threat … on the horizon” that was set to unleash “an ominous peril”. He said that Egypt will make sure to take measures to “uphold and protect the vital interests of its people”. It was thus through a veiled threat of war at the pulpit of the United Nations Security Council that Egypt transformed what has been a peaceful negotiation on the operation of an innocuous hydropower project into an issue of international peace and security. The disadvantages of a late-comerTo be sure, the negotiations over the Blue Nile dam have been daunting and slow, but it is far from true that the GERD would reduce Egypt’s water use. The hydropower dam in fact does not consume any water at all: it needs to let water through its turbines to be able to generate power. It is also only 20 kilometers away from Ethiopia’s border with Sudan, and in a mountainous location without any promise for future irrigation. If anything, it will reduce water losses from evaporation as its reservoir will rest on a highland area with deep gorges. By contrast, Egypt’s massive reservoir at its Aswan High Dam in the Sahara loses more than 10 percent of the Nile’s annual water flow to evaporation.

Ethiopia’s permanent representative at the UN, Ambassador Taye Atske Selassie, responded that his country did not ask too much of Egypt. It only asked for a fair share in the use of a river body that canvases the vast majority of its territory, and towards which it contributes 86% of the annual water discharge. Indeed, the GERD should be supported by the UN, which has embraced a global agenda for sustainable development. Enshrined in 2015, these UN goals aspire to achieve, among other things, universal access to electricity by 2030. By doubling Ethiopia’s power generating capacity, the GERD will extend access to affordable and renewable electricity for more than 60 million Ethiopians who still live in darkness.

An unfair mediator

Once again, much like during the times of Haile Selassie, this was a confrontation between David and Goliath, between the weak and the powerful. The indignation of Mr. Shoukry could not have been for lack of understanding that the GERD will not lead to an appreciable decline in the amount of water that will flow to Egypt. He very well knows that this project is within the acceptable range of equitable water use by Ethiopia, which he acknowledged is a principle acceptable to Egypt. His passion has most likely to do with the fact that a “small”, poor African country like Ethiopia dared question the wisdom and authority of his own country and that of Washington.

Under President Trump, the U.S. has played the role of Egypt’s right-hand in the effort to cement an Egyptian hegemony over the Nile. In November 2019, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi called on U.S. President Donald Trump to help broker an agreement on the Nile. This was done unilaterally by Egypt, and outside the negotiation procedures outlined in the Declaration of Principles signed between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan in 2015. President Trump is a friend and close ally of Al-Sisi, and has been overheard calling him his “favorite dictator” during the G-7 summit in Biarritz, France.A self-proclaimed dealmaker, Trump wants to garner recognition for a successful brokering role. He may also have an ulterior motive in resolving Egypt’s burning concern on the Nile dam. He badly needs the unequivocal support of Egypt in his “Deal of the Century” program for the Middle East, which has been roundly rejected by Arab nations.

The foreign and water ministers of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan have held a series of meetings in Washington since December 2019, and met Trump at the White House. In February 2020, however, these negotiations broke down when Ethiopia temporarily suspended its participation, requesting more time to deliberate on the draft agreement. Will the GERD be Ethiopia’s last dam?In the absence of Ethiopia, Egypt signed the agreement, which has been apparently drafted by the United States with the help of the World Bank, while Sudan refused to do so. Ethiopia’s foreign ministry expressed a disapproval of the draft agreement, which it considered unfair. Instead of helping resolve these differences as would befit a neutral mediator, the U.S. Treasury, which was in charge of these negotiations, openly stated that the draft agreement “addresses all issues in a balanced and equitable manner” and warned Ethiopia that “final testing and filling [of the GERD] should not take place without an agreement.” This unhelpful, partial role of the U.S. has been widely criticized by many former American diplomats.

Ethiopia fears that the draft agreement will effectively reduce the GERD to a mechanism of smoothing water flows to Egypt. It will lower the size of the reservoir by about a third, allowing for its filling by a maximum of 49 billion cubic meters (BCM) out of its full capacity of 74 BCM. In drought years, the GERD is to release ever greater amounts of water to compensate for the decline in the river’s flow, which could further reduce the dam’s generating capacity. Ethiopia was required to provide daily data on the river’s flow at the dam. Lack of compliance was to be independently investigated and resolved through an independent and binding arbitration. This levels an onerous legal demand on Ethiopia that entails strict obligation (in the form of a binding treaty), high precision (in the form of minimum guaranteed water discharge), and high delegation (through a binding, external dispute settlement). With increasing upstream water consumption and climate change, the flow of the Nile could well decline from natural causes below the minimum guaranteed release stipulated in the agreement. Ethiopia’s negotiators complain that the agreement will force Ethiopia to bear the full burden of future droughts, and, under some scenarios, leave the country in the odd position of owing water to Egypt. The flow restrictions will also make a future project on the Nile impossible, potentially making the GERD Ethiopia’s last major dam on the Nile. Changing that could require visiting international courts for a binding legal decision in favor of a new water allocation scheme. For proud Ethiopians, subjecting a dam they built with their own coins to such an intrusive Egyptian oversight is extremely unpalatable. The Nile Basin Initiative There are currently no legal mechanisms that govern sharing the Nile waters between Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan, and the remaining eight other riparian countries. In the absence of a preexisting legal ground for water allocation, Egypt is effectively using the GERD to institutionalize a binding minimum guaranteed flow that will protect its long-term water access. Ethiopia insists that this type of water allocation scheme should be made through an institutionalized, multilateral approach that involves all riparian countries. The Nile Basin Initiative, which was formed after extensive dialogue by 10 riparian countries in 1999, provides such a durable institutional framework for governing water use in the Nile. Its cooperative framework mechanism, however, has been stalled by Egypt’s insistence to maintain a veto power on all future upstream projects. Ethiopia was right to have walked away from the Washington negotiations since no agreement is better than a terrible one. Had it signed this agreement, it would have been forced to request a revision at some point in the future when its water demand increases or supply falls below the pre-specified figures. This would leave it at the mercy of a complex and potentially futile process of external arbitration effort to change existing stipulations. A war of water Egypt’s reliance on the Nile is undeniable, but its approach for securing access for its waters has been excessively zealous. It should be remembered that Egypt had sent military expeditions during the scramble for Africa to occupy the headwaters of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. Isma’il Pasha, who was the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan before the British stepped up their influence in the country, harbored the ambition of expanding his realm across the entire Nile basin and the whole African coast of the Red Sea. Having occupied the garrison town of Massawa on the Red Sea, which was then within the borders of Ethiopia, his army, which was led by European and American mercenaries, ventured into the better-defended Ethiopian highlands. It was met by the army of Emperor Yohannes IV, under the command of his famed general Ras Alula Engida, who repulsed the invading forces at the battles of Gundet in 1875 and Gura in 1876. Having safeguarded its independence so zealously over centuries, Ethiopia is hence unlikely to give away its sovereign rights over the Nile – a river endearingly called Abay in the country. A renewed negotiationIt is not without reason that the then Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Meles Zenawi, chose the grandiose-sounding adjectives of Grand Renaissance as prefixes to the dam’s name. He knew that Egypt would test Ethiopia’s resolve in all fronts, and adopted the name to underscore the centrality of the project to Ethiopia’s aspiration to extract itself out of poverty. It has become one of the most important unifying forces in the country, as epitomized by the flood of the twitter hashtags #itismydam that appeared in response to Egypt’s demand to postpone the dam’s filling until an agreement is reached.

The discussions are now taking place under the mediation of the African Union. Egypt did not trust the African Union, which is the reason why it preempted its involvement by going directly to Washington and then the United Nations. But if the goal is to reach a fair resolution, there are fewer alternatives as sound as the African Union. Under the principle of “African solutions to African problems”, this regional body has a better chance of providing a more institutionalized approach for the Nile dispute. This is hence a trying time for Ethiopia, as it was during the Italian occupation. By late 1940, as the Second World War was raging in Europe, the British Middle East Command initiated the East African campaign to free the region from Italian occupation. Haile Selassie, who waited in exile in Bath, England, finally got the military support he requested five years before. He returned to Addis Ababa triumphantly on May 5, 1941 backed by the British Gideon Force under Colonel Orde Wingate. To the emperor, patience paid off and his plea for help in his fight against colonialism was heeded. Time will tell if Ethiopia will be fortunate enough to find another friendly nation that can help broker a fair deal with Egypt over this age-old dispute over the Nile.

Addisu Lashitew

Addisu Lashitew is a David M. Rubenstein Fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution. He has previously held postdoctoral researcher positions at Erasmus University Rotterdam (The Netherlands) and Simon Fraser University (Canada). Lashitew’s research interest spans various topics in development economics, including firm growth and productivity, resource allocation, and economic diversification. His most recent research has looked into market-based corporate approaches toward sustainable development and poverty alleviation. He has actively published on the topics of financial inclusion, social innovation, inclusive business strategies, sustainable finance, and Base of the Pyramid strategies. Lashitew maintains teaching and research affiliations with the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) in Nairobi, and the School of Commerce of Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. Addisu Lashitew is a research fellow at the Brookings Institution. He can be reached at alashitew[at]brookings.edu